My salad days,

When I was green in judgment, cold in blood,

To say as I said then. – Cleopatra, Act I, Sc. 5

“As a great encounter between West and East as well as a great love story, Antony and Cleopatra enacts a basic pattern of colonialism. Shakespeare draws on a network of stereotypes when he shows orderly, ambitious Roman conquerors confronting exotically decadent, emotional Egyptian subjects.

Rather than asking viewers to suspend their disbelief, Antony and Cleopatra features characters who disbelieve their own presentations of experience and who somehow are all the more compelling for it. Shakespeare scours received myths with skepticism, and then audaciously presents them for his audience’s admiring participation. Shakespeare’s portrayal of the relationship between Cleopatra and Antony, and of that between Egypt and Rome, illustrates what Jacques Derrida calls différance, the logic through which two terms are caught in irresolvable dependency on one another.” Cynthia Marshall, Folger Shakespeare Library

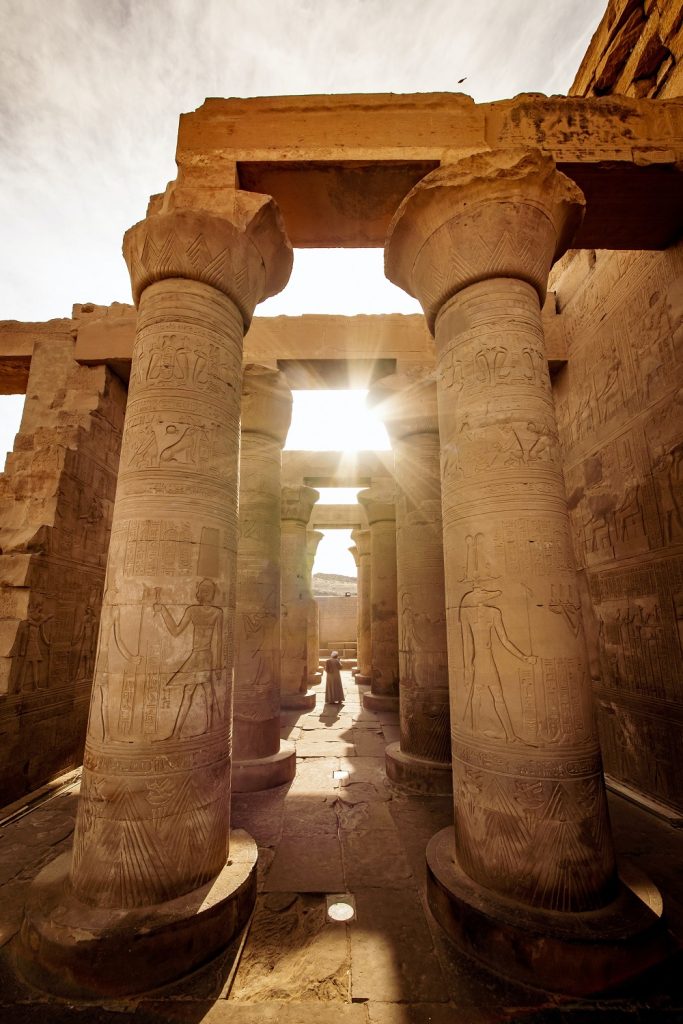

Antony and Cleopatra is a later Shakespeare play, written and produced in 1607, four years deep into the reign of James I. Like Timon of Athens and Pericles, Prince of Tyre, it stays in place for all the action, veering back toward the three Aristotelian unities (of time, place, and action, we get place and era, so I’ll count this as two out of three, which ain’t bad.) None of the dizzy jumping around we found in Cymbeline! Antony and Cleopatra is located in the empire of Augustus Caesar, bouncing back and forth between Alexandria and Rome, contrasting the uptight Romans with the sensuous Egyptians with plenty of cross-cultural commentary – my personal catnip.

I found a Royal Shakespeare Company production of the play from 1974, almost as old as I am, with some very good acting indeed, but the cherry on top was none other than Patrick Stewart, Captain Jean-Luc Picard, in a meaty supporting role as Antony’s right-hand man Enobarbas complete with tufty beard and receding hairline. I had no idea Patrick Stewart ever had so much hair! Production values for this piece were hilarious, taking me right back to a high school classroom in the eighties with a giant television on a rolling cart and a VHS player placed on a shelf below. This was Stewart’s breakout stage role, the one for which he was “discovered” as a stage talent. One of the true pleasures of the Shakespeare project has been the travel through vintage video to see famous thespians cut their teeth on the stage in a Shakespeare role. Stewart was born in 1940 and was this 34 when cast in this piece, but he looks every bit the grizzled part of a Roman soldier and old beyond his years. The Antony they cast was really overly grizzled, making it hard to imagine how a sex symbol like Cleopatra could be obsessed with this eyebrow-forward Roman chunk of dry-cured beef. But I digress.

The main thrust of the play centers around ego and reputation. Antony and Cleopatra: outsized characters on a world stage. They abuse privilege and are immature. Antony puts Cleopatra before his job as a Roman general and triumvir of the Second Roman Triumvirate, annoying Augustus, who summons him back to the mother ship in Rome. The joy of Antony and Cleopatra at the unexpectedly handy death of his first wife turns into dejection as Augustus helpfully marries his sister Octavia to Antony to keep him closer in the family, as it were. She fails at her interfamilial diplomacy and Antony, back at sea, finds that his battles go awry. No action finds success.

Antony turns on Cleopatra and assaults her. She shuts herself up in a monument and fakes her death. This is where things get very Romeo and Juliet. Antony thinks she really IS dead, of course, so he tries to kill himself. He’s bleeding out when a messenger comes to say, by the way, Cleopatra is NOT dead, but it’s too late for Antony. He’s misjudged the situation on every level – poor skills indeed for a military leader, and a compelling illustration of how things went south so fast for the man. A troop of soldiers bring the not-quite-dead Antony to Cleopatra so he can die in her arms.

Augustus sees his chance to grab Egypt – and the beautiful Cleopatra – for himself. He’s got plans to shame Cleopatra, who of course cannot countenance it, and she gets a local farmer to bring her a special basket of figs including one very poisonous snake. (I’m sure you have heard this story.) Cleopatra plays with the snake until it bites her and she dies. Well played, Cleopatra, well played. Augustus is at pains to admit that she got the last word in, in the end.

The play offers psychological insights to the construction of reputation and ego, and what happens when those constructions unwind and collapse. The Roman theme of honor runs strong – once honor departs, the only option is death rather than a dishonorable life. Got a lot in common here with Japanese cultural and literary values. The treatment of these themes, however, keeps the play relevant to this day. In fact it might have been due to the extremely camp Etonian actor cast as Augustus, but I kept coming back to towering British figures in the late modern era and feel they are ripe for stage reboot, in particular Boris and his current wife, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak. These characters seem more like caricatures than people with genuine motivations. What is lost when reputation is lost? Is a dishonorable life worth living? What happens when we cannot wring external circumstances to match one’s internal expectations of How Things Should Be, and how the world should receive you?

(This also makes me think of some managers I have known in US work culture in my own salad days. Bent on making an always-favorable impression while always getting their own way, but this does not continue indefinitely as public opinion sours and outsized egos become enraged at the unfavorable reception of their formerly lauded identity.)

Funny side note: I always thought salad days referred somehow to abundance, but the actual reading – being green, and therefore young, with a naivete that bolsters cold blood and cold decisions – strikes me as much more accurate and poetic. The true tragedy in Antony and Cleopatra lies in the fact that the world is their oyster (thank you, Merry Wives of Windsor, for this idiom), yet they squander it all, and then snuff themselves out. And in this the theme is found to be modern and relevant indeed.

Moving on to All’s Well That Ends Well, which I do not think I have ever read! I believe it is also the “lost” companion sequel to Love’s Labour’s Lost, which ends abruptly just as the flirtations within the group were getting good. Gonna get out of Shakespeare’s Mediterranean!

After that, two more history plays to go (Henry VIII and Henry IV, Part II) together with King Lear (never read!), Othello (know well), and Coriolanus (virgin territory).