I’ve been thinking a lot lately about cultural expectations – what someone might reasonably expect to happen on a daily basis, living within a culture, and further, which expectations might fracture when the plate shifts, and someone from Culture A finds themselves more or less immersed in Culture B. We are all products of our culture, whether or not we recognize this, and I grant that it can be very difficult indeed to recognize this fact if one has never lived anywhere but in one’s own culture, leading to the assumption that all expectations everywhere match the ones from inside the bubble.

I have written here occasionally on sociopolitical topics, but my first year in Firenze was more a fat pipe of beauty: see pretty thing, take pretty picture, share. I do love catching a breathtaking image on my scurryings about town on my various daily errands – school, work, choir, church, dentist, and more.

But now, halfway through year two, I find myself noticing and comparing the cultural data I have been accruing here through experience, and comparing it with my cultural reference section, abundantly shelved thanks to my career steeped in US immigration and academic immigration, and time spent living abroad and traveling, but especially Spain, France, and the UK. Because I lived for thirty years in Oklahoma, and left not quite two years ago, those cultural reference volumes in particular bear recent evidence of perusal.

I’ve indexed some of these mental notes and comparisons, and present one of them below for my audience: American aggression.

I am unsure if this phenomenon can be ascribed more to Oklahoma. Perhaps so, as I noticed far less of it in the more civil Pacific Northwest, and even in DC and NY, all places I have lived.

America is not only a frequent global aggressor, what with our various bright ideas for deploying military power, but internally, America is an aggressive culture. Part of this is due to the omnipresence of firearms, in open or concealed carry, or illegal carry. In the US, I was terrified of any dispute’s escalation. A gun was a very likely possibility.

In Italy, gun control is sound, and logical. In fact, I have never thought anyone would pull a gun in the EU, and I am glad for that. Not even in Finland, which loves hunting, and is currently ranked by the UN as the happiest country on earth. My Finnish cousins in Karelia with their gun racks are not proponents of a firearms free-for-all. (In my perfect world, no one would hunt, but I do not get to make up all the rules around here. I kind of wish my great-grandparents had not gotten on that boat headed west from Liverpool, but that is a topic for a different day.)

An illustration of my cultural conditioning. One day last fall in St. James, I was either serving or singing, so was in the chancel during mass. A man came in halfway through the liturgy, alone. With a backpack. Of a certain age. Of course he was a tourist, but I have been so conditioned by the lack of public safety in the US that I actually began to have some version of a panic attack sitting up there. He started to fiddle with his backpack; he wasn’t paying attention. But in my reptile brain I felt pretty certain that Backpack Man had weapons in there, and my palms began to sweat. Why is an usher not approaching him, or asking to check his backpack? I thought. All the other Americans in the building were facing forward and paying attention. Someone should really ask him to sit down, or ask to check in his backpack, I thought. I tried to mentally convince an usher to do so, as my imagination was working overtime and I was picturing him pulling some gun out of the backpack.

But no. It was fine. He was just a middle-aged tourist with a grey ponytail, and a backpack. He was probably looking for his guidebook to figure out where he’d just interrupted mass. He left a bit after, never having sat down, but neither having shot and killed anyone either, even though in my mind this had been a distinct and panicked possibility.

This reminded me of my time working on campus. I had two offices at OU: one was in an old building, the floorplan like a glorified hallway, with a front entrance and a hallway to another door. We had a few really disturbed international students, unstable young adults on the edge (one non-traditional woman in particular), with no-trespass orders on campus and police involvement, but I always thought in my mind, I can get out if someone goes nuts in here and becomes violent.

The other office, which I spent six years working in, was a renovated classroom, with one entrance, and this setup scared the daylights out of me. Happy international students did not typically come to our office. It was the ill ones, the failing ones, the struggling and depressed ones, the irrational ones. The office had one entrance, which was also its exit, and that was it. If someone came into our office with a gun purchased at a gun show, ready to teach me and my staff a lesson, there was nowhere to go or to hide. I literally sat at work and imagined the ways I could seek refuge under my desk, or in our supply closet where we also pumped breastmilk.

I calculated how long it would take an armed student to find me and shoot me. How long would I have to stay under my desk, could I convincingly play dead, or would an irate student come looking for me by name? How far down was the jump from the second story? Could I break a window and climb down that juniper tree? Probably not in time, but these calculations nevertheless spun through my head. This thinking was sick. But I did not feel safe, we did not feel safe, and that seemed to bother no one but me and my staff. Again, and to clarify, most of our 2,500 advisees were just fine, but we had five or so each year who seemed to be on a literal hair trigger.

This type of public violence did not seem to happen when I was growing up in Oklahoma and Michigan. The first mass murder by gun was in Edmond, OK, 73034, at the post office just a mile from my school, in 1986 or so. We were in shock for weeks. My mom understandably freaked out and didn’t really want us going anywhere, which was more a punishment for me than my two brothers, who tended to stay home anyway.

There was bullying in my high school, but it seemed limited to skinheads versus skaters. I remember a fair amount of very Mean Girls-style bullying in the seventh grade, but no one ever thought that someone would bring a gun to school and shoot everyone, at any time, in my schooling.

Gun violence doesn’t just start with guns. It begins in a culture of aggression and bullying, where might makes right, and boys are bred and raised to be big, and therefore stronger, and therefore dominant.

In preschool in Norman there were six and seven year old boys in Victor’s pre-K class (which should have all been kids who were four, turning five) who were specifically held back to grow bigger for football. This is madness. Note that girls were never held back for this purpose, as it was strictly gender-driven, and, I might argue, race-driven, since these little boys were almost always Anglo, creating a miniature ruling class of dominant males right there in pre-K that would persist in the culture in all cohorts, at all levels, for years.

I talked to the school’s director about it, and was told something along the lines of, parents have a right to hold their children back.

Um, yes, I thought, but not for sporting reasons, and those boys should not be permitted to become the bullying terrors of the class. I was just sick about it in the fall of 2015. I did not want our children to be raised in a world where this seemed normal to them, where they had to learn to protect themselves because the adults in charge indicated they were powerless to change the rules, and thus the dynamic. This was the same school where I was told that conceal carry was the law in the state, and so the private preschool would make no rule otherwise prohibiting parents from toting their pistols around in the school. This was the same year where our small children were in lock-down three times for gun-related violence.

Conversely, the adults in charge might well be aggressors themselves, as with the neighbor in Norman across the street, who I saw one morning chase his son around their car, catch him by the arm, and hit him again and again until the little boy was sobbing. I saw all this from my window, like a terrible stage piece, but did not go out to confront the father because I assumed he was packing heat.

I had been raised in such a world, and had adapted by developing strengths in skills of “freeze and friend”: smile at the big boys, they might decide you’re harmless, and leave you alone. Play dead with a weird sort of frozen smile. Do nothing to provoke. Do not challenge. Crawl under the desk and play dead. Disappear. Become silent. Keep your counsel at all times.

You never see kids held back for sport in Italy. The Italian parents here actually think that soccer is a dangerous and violent sport, which really makes me laugh. The US from Italy seems like a version of Sparta on opioids, which is another topic for a different day. The overall atmosphere in the children’s school in Florence is one of sane adults in charge, and I have noted little evidence of bullying. Italy, on the whole, and in this context, persists as a civil society in ways that America does not. I am sure bullying happens. I am sure it is pervasive in less well-off communities; Florence is arguably an Italian center of wealth concentration. Any Italian will tell you that the Mafia and Comorra and ‘Ndragheta are bullying shadow institutions.

I re-read 1984 a year ago, looking, in part, for a playbook. Orwell does a superb job describing citizens cowed by culture, products of fear and conditioning.

An Italian woman asked me yesterday to explain what is happening in America. I was late for work, and could not. I said, it is a big problem, a huge problem. I am glad to be in Italy where things seem to work.

Ma che! her eyes grew wide. There is plenty in Italy that does not work! she told me.

Yes, I said, but you have a civil society.

She looked dubious.

Things work here, I pressed. I listed their universal healthcare, pensions, schools, nice roads, bridges that do not fall into rivers, the luxury of feeling safe from harm in public, which should be a primary civil right, but for Americans in America, it cannot be had.

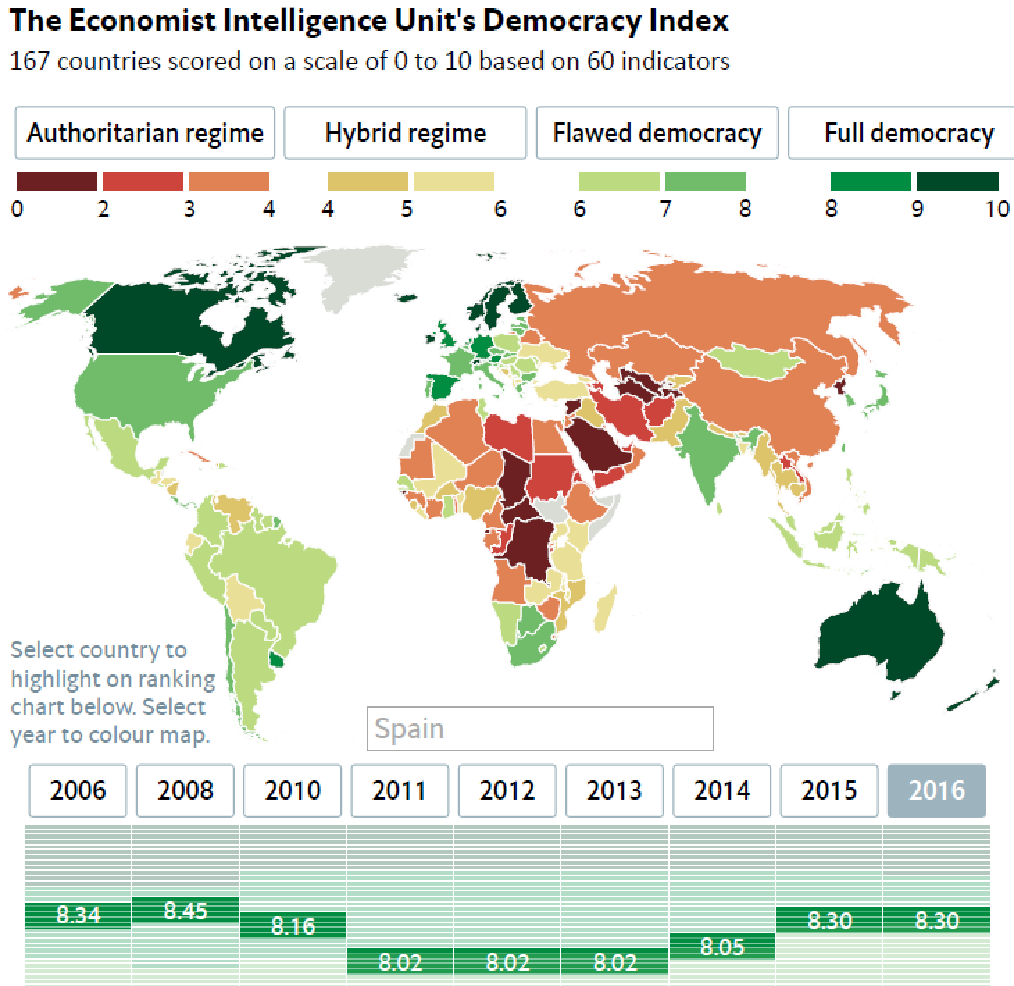

In Italy, I said, people are kind to each other. There is a sort of kindness here, of life on a human scale, which America has lost. But also, I added, the US, Italy, and Poland are all on a list of flawed democracies. I understand why Italians are upset.

Italian electoral rules seem to be of a piece with American gerrymandering, and a fair amount of election confusion. The voting rules are so complicated that no one can make sense of them anymore.

Worse, people vote, and then some other process blender takes over to assign percentages to their governing bodies based on the multiparty election results. Errrr.

There then ensued a long linguistic discussion of what flawed meant, and how to spell it, and when to use it.

She said my scarf looked pretty.

I do not think Italians love hearing Americans list what appears to be functioning in Italy.

I am still decompressing here from my time in Oklahoma. I know we are privileged to live here. We had the option to leave, and many do not. Everyone in America is compressed, with little sign of decompression possibilities on the horizon. My heart aches for this fact.

Hear me: It does not have to be this way. It does not. It is not this way in so many other places. The predominant culture in the US right now is not an inevitable reality.

Further topics for this discussion: Italian rules that can be broken, Italian vending machines, the school menu and nutritionist. Much more anodyne topics, unless someone out there is really feeling this soapbox.

One Response

Regarding aggressive culture in the USA: I had drinks with two friends last night, and one of the topics was games, both video and board. One friend had talked with a couple of Nordic programmers who had come to the US to work in video games; after a couple of years, they were ready—and later, anxious—to get back to Europe and away from American video games. My other friend has gotten quite absorbed by board games, and he said “Eurogame” was a thing, distinct from American games, and distinguished by relying more on cooperation than domination or destruction of opponents.I see that Wikipedia is aware of this; the description of Eurogame says: “A Eurogame… is a class of tabletop games that generally have indirect player interaction and abstract physical components. Euro-style games emphasize strategy while downplaying luck and conflict. They tend to have economic themes rather than military and usually keep all the players in the game until it ends… Eurogames are sometimes contrasted with American-style board games, which generally involve more luck, conflict, and drama.”