Last week I went to hear speak an author whom I adore.

The inimitable Sarah Dunant.

Venue: British Institute.

Time: Dopolavoro.

Transporte: Bici.

Compagnia: Nessuno. Just me.

As with the cena delle mamme, I almost bailed a few times, and Jason urged repeatedly to go. We have a lot of back and forth like this on Messenger:

Monica: I don’t know. I don’t know if I’ll go.

Jason: I think you should go.

M: I am tired. But I have been talking about this for weeks.

J: Please go.

M: I don’t know.

J: Go.

So I pedaled across il Ponte Santa Trinita, down the Lungarno Accaiuoli, eyes peeled for the British Institute. Number 9 red, number 9 red, I chanted to myself.

I finally stopped at a full bike rack to lock up my bike, certain I had just passed it. Then I saw an older woman, and then another, dressed in the style of what a friend once called Urban Prophetess, but which is properly purchased at a store like Chico’s, and their short, straight, white haircuts with bangs immediately gave them away as English Women of a Certain Age. Like a younger American pilot fish, I quickly slipped into their wake, feeling the heft of my backpack with my entire office in it plus a fat newish book for the author to sign.

Side note. What is it with the haircuts, Women of England? Is there a National Haircut System, where bureaucrats assign women a certain haircut after a certain birthday? If so I want to see the catalog because I think it is one page long. It’s like Sister Wendy sans headgear, or Mary Beard. I am not saying I do not like these haircuts per se, but it is rather their consistent deployment as a cultural marker that makes me pause, a bit like a Canadian maple leaf patch that has been hand-stitched onto a backpack.

Back to topic. I arrived with a small wave of older Brits, borne by the wave into the foyer, where they all deemed the stairs too steep, even though the older Brits all seemed rather spry to me. They waited for the elevator while I took the stone stairs up, since the doorman had just assured everyone that the steps numbered just 51.

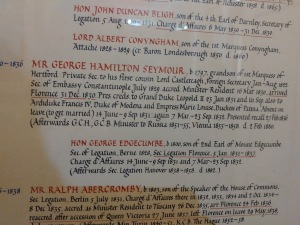

|

| Bit o’ institutional Brit pedigree while you wait! |

At the Ferragamo library a small group to enter. I could already feel the heat of exhalation coming from the tall reading room; I caught a glimpse of a carved and painted wooden ceiling. There did not appear to be much room. Wow, so, like, 100 people had gotten here before me, average age: 65. I shifted my backpack as I was informed that the event cost 6 euros.

“It includes a very rich buffet!” the woman informed me brightly in English.

“Ma certo, siamo in Italia, certo che il buffet e ricco,” I replied.

“Ma non, non e sempre certo,” she responded. “This one really is rich.”

I collected my receipt and went into the large room to stand awkwardly at the front. I was a bit peeved they’d oversold. Soon, a woman came in and pulled very large, carved wooden chair over for me. I sat in it. My feet didn’t touch the ground. I adjusted my backpack to be a footrest. The older American couple to my left struck up pleasantries with me, and the topic turned, as it inevitably does whenever two or more Americans are gathered, to healthcare. We discussed doctors and insurance, providers ad hospitals, ASL and America.

“How do you know so much about this?” they asked me.

“I really don’t,” I effaced. “You should meet my husband, he’s practically health minister. But really, we’ve been traveling in and living in Italy for years … so I guess it is fairly accrued knowledge.”

“How many years?” they squinted at me.

“Oh, at least … twenty. More than twenty.”

“Did you start this business of Italian traveling when you were, what, two?” the husband croaked.

“Keep it up,” I laughed.

A few more people piled in and were assertively seated. Sarah Dunant was introduced by assorted Important People, and she set to lecturing.

I had read her fiction for the first time in 2005, The Birth of Venus, about Artemisia Gentileschi. I was a page turner, and unlike anything I’d really read recently, at that point. This was the summer we first lived in Firenze, in our ground floor apartment in Le Cure. I read everything in that apartment, and when I ran out, her novel was one of the books I bought.

I saw her upcoming lecture advertised in The Florentine, and resolved to go. I saw she had a new novel out, and after some prowling in centro, purchased it, and began to read it.

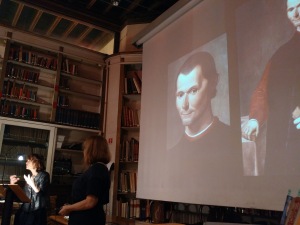

It was really worth it to attend. Wow – what energy, such creativity and intelligence. It was so worth the solitary post-work effort. Slides and jokes, her new book being about the Borgias, she had plenty to say about Trumpian parallels, which was met with general grunts of approval and a slight smattering of applause. She really burst with energy. I was smitten; I am always on the lookout for an authorial hero or heroine.

|

| The author, plying positive publicity, and honestly enjoying herself. |

|

| This way to NOT go to the Rich Buffet. |

After, she took questions, which amused. I stood in line a bit for her to sign my book. More than a few of the Haircuts cut in front of me with their newly-purchased copies, but I didn

‘t care; I was enjoying the ceiling. The husbands of the Haircuts had immediately headed into the other room to make short work of the rich buffet and its accompanying prosecco.

It was my turn! I was on script. “Love your work,” I said. She was gracious and started signing. I asked her then about the dedication in the book, and we chatted about her History tutor at Cambridge. She seemed glad I had asked her about him. “Oh yes, my tutor! Died far too young,” she clucked. “Retired at 54 to write and write, and fell off of his bike, dead of a heart attack, two months later. Smartest man I’ve ever known. Just full of knowledge.”

Book in hand, I stepped out, and quickly surveyed the Rich Buffet, which could not even be seen behind all the bodies. I snooped around the building a bit before going down the 51 stairs and back to my bike, and then pedaled home in the Florentine dusk of a perfect early spring evening.

|

| Sera fiorentina |