In social situations, who gets to avoid embarrassment, and who bears the burden of embarrassment? I suppose this applies to many different types of circumstances, but I am here specifically considering language learning and the stress of immersion acquisition.

I will explain the rabbit hole.

I don’t want to speak English, say some Italians. Il mio acento è bruttissimo. My accent is very, very ugly.

This always makes me laugh, then cry. I, who bear an accent in Italian that must sound something like a Valley Girl ca. 1984. My main evidence for this is the mockery of the polizotti at the questura in January 2017. I don’t mean for this accent to happen, and it was never an issue for me in Spanish, where my immersion acquisition foray into Spain in 1993 spit me out with a near-perfect accent (in my mind) at the end of six months. Why can’t my Italian sound more like my Spanish? ¿Por qué no?¿Por qué?¿Por qué?¿Por qué?

Then I panic. How ugly is my accent in Italian really? Do my vowels make native speakers cringe, the way I fumble for consonants? Are they all thinking, she seems quick enough, but oh my god that accent is like nails on a chalkboard. I fear this in my more anxious moments.

Then I think, wait, if they think MY accent is annoying, why do they let me keep talking? That’s it. I’m not speaking Italian again.

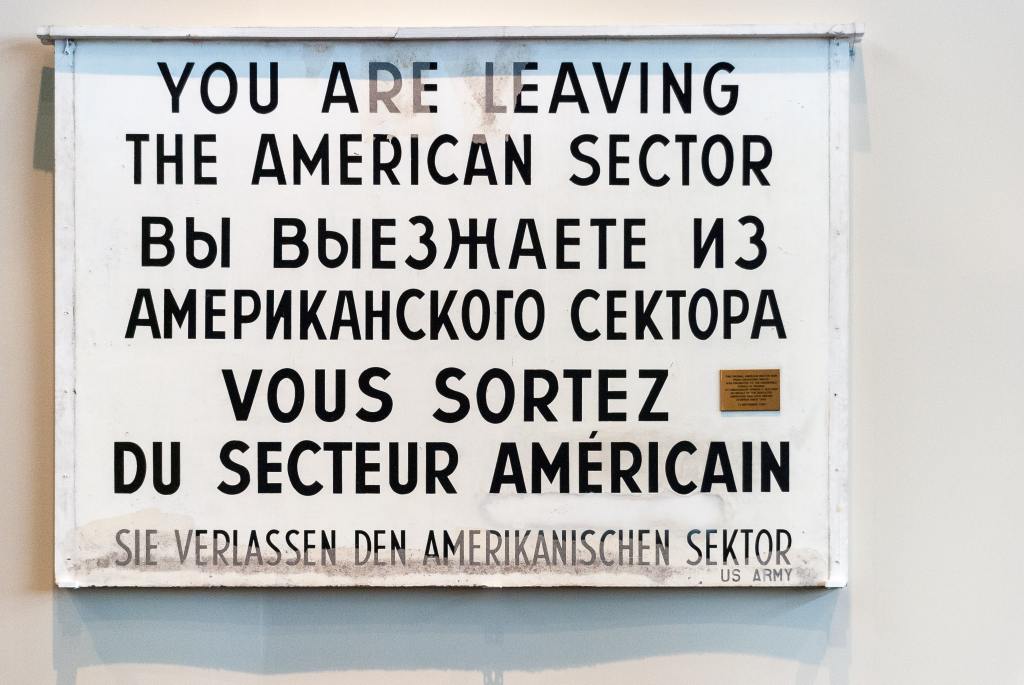

Then I think, they must think people are so mean. This makes me sad. I explained the other day to an Italian friend that it is almost impossible to speak English with an accent that a native speaker would pretend to absolutely not understand. English offers a marketplace of global accents, all comprehensible. Maybe Italian doesn’t exist in enough accents.

I am thinking of Italians who won’t speak English because they are quite certain that native English speakers are quietly mocking them, which is not happening. Instead they would rather their interlocutor speak an accented Italian.

Immersion acquisition is the sink-or-swim model of language learning. You go to the place, no one speaks to you in anything other than Language X, which is not the language you were raised speaking. This was a honorable way to learn language in horsey times before the interwebs and dumbphones existed. Eventually, over time, and frankly over a lot less time than sitting in a classroom, you remember words and phrases and pronunciations, verbs and tenses and the rules around the subjunctive and formal usage. These lessons are engraved on your brain, the synapses knitted closely together in a tight dance of emotion and language. I’m no neurologist, but as a lifelong language learner, I can say that without feeling there is no language. Perhaps language can exist without feeling, but it sounds a lot like that weird male voice that reads PDFs out loud for me sometimes on accident and I still don’t know how to make that happen on purpose.

At any rate, without having a feeling about whatever linguistic point I was learning – really any feeling at all, so long as it was a good strong one – there was virtually no chance that the lesson would stick. The word would be lost, the verb forgotten, the tense misused yet again. Someday I will catalog a list of language learning highlights that stay with me today, particularly ones about oranges, lollipops, and the subjunctive tense that expresses a set of circumstances that will never, ever happen in this lifetime. Some combination of joy, fear, elation, shame, wonder, even a warm-natured pedantry can work; for example, I will never forget how to say “sunset” in Spanish after a kind older Gallego sitting on a long stone bench with me in Santiago de Compostela admired the sunset with me, and seeing that I fumbled for the word, intoned la puesta del sol. In that moment, the magenta-streaked sky, the cool air, the kindly man in his cloth cap, the hard stone of the bench, all converged to make sure I never forgot this term.

You really have to be willing to put aside your fears and never stand on ceremony. A language tiger must wade in, chin up, ears open and pricked up for clues, eyes scanning the near and far horizon, her language whiskers attuned to usage and intonation. It’s not easy. It is, in fact, exhausting.

One summer in Finland, my cousins looked at me pityingly and said, You must be so tired, listening to us, in spite of our mother’s warm cinnamon buns and hot coffee. Go take a nap. And they were right. It could have also been the marathon of Formula 1 they were watching in the living room with Finnish commentary. I trundled off to a guest room, lay down on a twin bed with a cotton coverlet, and had the best nap of my life. Listening in that state of high alert with your toolkit of feelings at the ready to be deployed in the service of effortless remembering – because memory is the better part of this enterprise – is exhausting, like the beginning stages of any relationship.

All this to say, feel free to be embarrassed. It will lock in some language, if you’re trying to learn one. I am sure of it. Then, after a long day of navigating one or more languages, go take a nap, if you can.

One Response

One of my favorite quotes:

Do you know what a foreign accent is? It’s a sign of bravery.

Amy Chua