Readers, you know how much I love to read. I also love to read really good fiction. I take no pleasure from reading genre fiction, as trite and as blind as it so often is (although I do love good genre nonfiction, like auto/biography, and true crime). If I do not like a book, I will put it down. I am a slave to the Hook.

I love someone who wields words naturally to tell a story that is new yet familiar. I crave a skilled author’s insight, their perspective. I want to see their story through their eyes. I love learning about their life, where they lived, who they knew, what they said. Who fought with whom, and who made up? Who succeeded and who suffered in life? Who kept the secret to the end, and who freely confessed? It’s exhilarating like nothing else for me.

Elena Ferrante and I were a writer/reader match made in heaven. just waiting to happen.

I first read the New Yorker article about her in early 2013. We were living in Arezzo then. I bought Days of Abandonment and My Brilliant Friend from Amazon UK. The article led with DOA, and I tried to read it first. Gritty, filthy, painful, angry fiction. Wow. I was not prepared for this.

I first read the New Yorker article about her in early 2013. We were living in Arezzo then. I bought Days of Abandonment and My Brilliant Friend from Amazon UK. The article led with DOA, and I tried to read it first. Gritty, filthy, painful, angry fiction. Wow. I was not prepared for this.

I put it away at about page 35 and did not open MBF. Maybe I was not cool enough for Elena Ferrante. This is what everyone was reading?

I’ve been a New Yorker subscriber since … 1994? A while. I felt like I’d been suckered in again by East Coast literary tastemaking and aesthetic arbitration.

I might have started MBF, but it starts out so dark and creepy. Sigh. I put it down, true to form. When we returned to the US, I brought the books back with me.

I have a friend, Alise, in Norman, also an intrepid reader. “Pick it back up!” she urged me repeatedly. “You won’t regret it.”

“Yes, but I am just trying to finish this 1,200 page novel that barely qualifies out of the genre fiction category.” (Genre: romance and adventure. I was deep in my 2014-2015 Outlander phase.)

I put down book 5 of Outlander (The Fiery Cross) and picked up my copy of The Goldfinch. I love Donna Tartt, always have. Goldfinch was tough going, and depressing. I told everyone I was reading The Sadfinch. Another story that everyone loved. What was wrong with me, as a reader? I trudged through it, complaining to myself, and internally, to Donna Tartt’s editor. I really did not like Sadfinch until about three-quarters of the way through it, then it caught fire for me and it made sense. The preceding 600 pages made the last 200 worth it. I internally apologized to Donna Tartt’s editor. She was right. It was perfect as is. (Maybe a tiny bit of editing around that lengthy “drugs in Las Vegas” component, but ok.)

I picked up MBF again this past spring. Encouraged repeatedly by Alise, I needed little further after about page 50. Wow – what a whirl. This book is incredible! I said. I gobbled it up, carousing around Naples in the fifties with my narrator, feeling like I had hopped into a time machine of culture and zapped straight back to the postwar mezzogiorno.

With swift, broad strokes, and absolutely no hesitation, Ferrante painted for me a tableau of lives interwoven and tangled so compelling, so clear, I did not even need the character notes at the front of the translation that had been helpfully placed there by the American publisher. Her narrative voice pauses for thoughtful insight, but when it is painting action, she is all Stephen Crane, with the Italian sleekness of a literary Brancusi.

The next three of her Neapolitan novels were all in the Norman Public Library. Brand-new copies on the “New Fiction” shelves. I checked out all of them. No one else was reading them. Unbelievable. I took them home in sheepish anticipation of how much I was going to enjoy this literary binge.

The books are substantial. They’re not light reading. I am a fast reader, and each one still took me at least a week. They’re long, and good, and they make sense both individually and as a whole. After MBF, I gobbled up The Story of a New Name (which Alise had helpfully prepped me for by saying, “It’s all horny teenagers, you’ll love it.”) Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay. The Story of the Lost Child.

Anyone who has grown up, who has moved somewhere, who felt like they did not fit in, in important ways, with the people with whom they grew up, and yet they share critical, sometimes shameful, qualities and values with them. As we were on the cusp of exiting Oklahoma, I thought, and wisely, that the books would help me process, in a compelling and parallel way, my feelings about where I’d grown up, and what it would mean to really leave it. And so it was the case. Ferrante’s Naples became my Oklahoma City. I had an ally in this. Ever since I learned how to read, I have always felt I have known authors personally: that they became my friends after we spent such intense time together. And so it was with Ferrante.

What I had not counted on also receiving in the exchange was a coherent explanation of new motherhood for a certain type of person, which struck a chord for me. The books traced a path around an Italy that I have come to know increasingly well over the past two decades, from Naples to Firenze to Milan to Genoa, with characters and dialogue whose verisimilitude I never doubted for a moment. Ferrante has helped me understand better the arcs of certain people and friendships in my life.

Seriously – does Ferrante even take a breath when she is writing? Her narrative is seamless, never stuttering once. Even when, for example, she jumps nine months forward through an entire pregnancy, explaining nothing, as a reader it made perfect sense to me.

I finished book four on a rainy April Sunday in Oklahoma, in a living room that was rapidly emptying of furniture and things. Reader, I wept at the end. The last twenty pages were like being at the funeral of a very stubborn old aunt named Hope. No spoilers here, but there is no redemption. Two thousand pages of glittering fast fiction buildup, and it ends with the proverbial whimper. In this, the despair is very much in keeping with the Italian shrug. Magari. Non si puo aiutare. This also helped me prepare for our move.

I did go back and read The Lost Doll, a novella which seems like it may have been the basis for the beginning of MBF. Lost dolls, and dolls and what it means to live life as a woman, and especially as a clever woman (Lena), in a chiaroscuric comparison of success and stymie (Lena and Lenu). How failure and endless high wall of culture will frustrate and twist and warp an intelligent woman (Lenu). How the protagonist lied to the family about taking the doll. How that doll vomited up rancid black ocean water when she attempted to give it dollie CPR. I’ll never forget.

I still haven’t read DOA.

I bring up Ferrante often, to see if people have read her. I do this a lot when I really like an

author … “So…” I have made some good friends this way, via Ferrante, and also Gabaldon, and Kundera. Others.

I wish that the popular media would leave Ferrante alone. Much has been made this month of her “unmasking,” of her “true identity,” of what she “owes” readers. Some people become crazy when they overidentify with an author or an actor. They feel they are “owed” something in return for their obsession. I have never felt as though I were owed anything beyond what I have received as their art – is it not treasure enough? Leave her alone, people, we need her to keep writing. Her voice is so important.

Two final points here:

Italians barely know Ferrante. She is huge in the anglophone world, and when I ask Italians, educated Italians, Florentines, the occasional napolitana or romana, have you heard of Elena Ferrante? They screw up their brow and say, who? Every time.

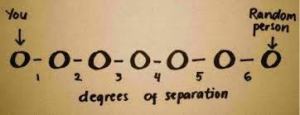

Jason disclosed to me this weekend that we have an unexpected three degrees of separation from Ms. Ferrante. What! I shrieked. (No, I am not going to stalk her. Never would.) An Italian friend of ours, who is well-placed in government, about our age (don’t ask, this is how my husband rolls), had the author’s mother as a high school teacher in Rome in the eighties. The mother was apparently very much loved, and universally admired by her students.

“This makes so much sense in light of Ferrante’s treatment of the relationship between teachers and their students, I said. “A whole life of framework and context when the student is attentive and the connection is there. … I still can’t believe you haven’t read Ferrante!”

“I don’t read anything after 1500,” he replied. That is what he always says.

So, with respect to three degrees, I counted it up, and it is:

>Jason and Monica

1

>government friend

2

>mamma di Ferrante

3

>Ferrante

One Response

Very nice Monica! And now I'm 4 degrees knowing you. -Alise